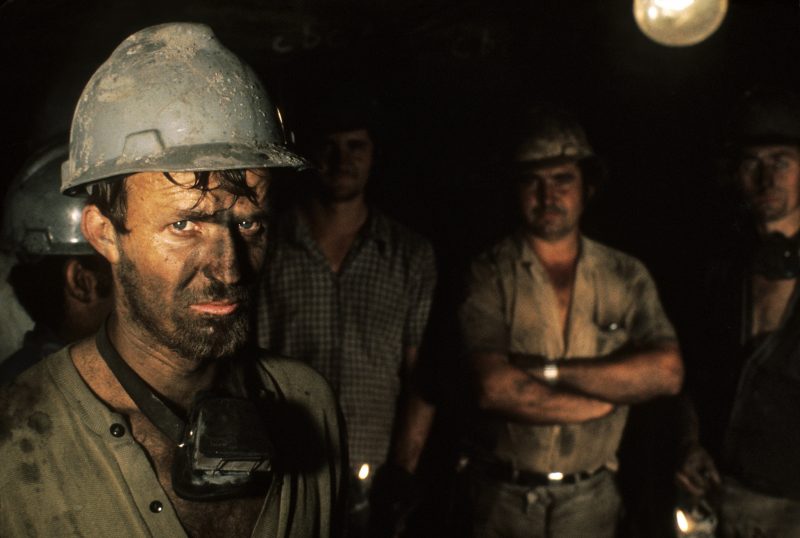

Putting miners at the heart of the just transition

The green transition needs resources and rare minerals - so how can we make sure producers of these critical resources are fairly treated?

The scramble for so-called transition minerals is on. If the world is to achieve the UNFCCC Paris Agreement climate targets, new technologies and a massive expansion of renewable energy will require more copper, cobalt, lithium, graphite, rare earths, tin and nickel. Global demand for these minerals will grow on average by 400-600 percent over the next decade, while for minerals like lithium and graphite used in electric vehicle batteries, the leap in demand could be as much as 4,000 percent.1

These minerals are found in significant quantities across the Global South, often in counties with poor governance, fragile environments and high rates of poverty. Expanding production often has serious impacts, leading to environmental damage, increased risks to the health and safety of miners, worsening the conditions of communities in and around mining areas and encouraging child labour. Historically, mining has a poor record of delivering inclusive and equitable outcomes. Unequal distribution of benefits, dispossession of natural resources, breaches of human rights still stand in the way of communities and producing countries benefiting from the resources, under their feet.

So, what would it take to turn this new gold rush into a win-win? Could we get the minerals required for a green transition while benefiting local communities and the environment, rather than exploiting and degrading them? Putting workers and community perspectives and environmental impacts at the heart of government policies and corporate practices along the supply chain offers a way forward.

The policy landscape

A range of voluntary international and national initiatives already exist on responsible mining and minerals. For example, the OECD Responsible Minerals guidance, published in 2013, is the basis for many government policies and industry standards such as the Responsible Minerals Initiative RMAP assessment. While there has been little assessment of the success of the framework in delivering responsible minerals extraction, it has at least increased the transparency of supply chains somewhat and drawn attention to workers’ rights and environmental degradation.

The Chinese are key players as producers of batteries and technologies for the energy transition. However, their business practices have been criticised as lacking transparent contracting, failing to comply with national regulations and environmental degradation. China has worked with the OECD to develop their own set of due diligence standards but enforcement is weak, with disputes between companies and communities often not worked out rapidly or effectively.

“ If the green energy transition is to live up to its ‘Just’ ambitions then the perspectives of miners and mining communities must be brought to the table.”

Governments are also beginning to regulate for responsible supply chains. The EU Conflict Minerals regulation, for example, covers tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold and is currently being expanded through the Battery Passport regulation to include battery minerals such as cobalt and lithium. So far, the US has focused more on securing supplies (eg: through the Critical Mineral Independence Act of 2022) rather than legislating for responsible supply chains. However, many American companies sell into European markets and must therefore comply with EU regulations, so are starting to engage on responsible supply chains.

Focussing at the local level

However, the reality of supply chains means that these efforts will take time to affect those impacted on the ground, so at IIED we are also working locally to support a win–win.

To take just one example, cobalt is a key mineral for batteries. An estimated 80% of global cobalt supply comes from the DRC, of which 20% comes from Artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM). These miners are often working in unsafe conditions and locked out of formal markets. Some companies will not accept ASM cobalt in their supply chains for fears of child labour and environmental degradation, which drives the miners to sell in informal, unregulated markets where prices are lower.

IIED is bringing our experience of engaging with local communities and ASM miners of gold and precious stones in other countries, organising multi-stakeholder dialogues to build mutual understanding, improved relationships and collaboration to deliver policy and practice improvements, with miners and communities’ perspectives at the centre.

This fed into the Cobalt Action Partnership initiative of the multi-stakeholder Global Battery Alliance to support the development of ASM cobalt supply chains that are transparent, verifiable, and address child and forced labour, and development issues such as gender equality, environmental protection and livelihoods. We are also working with a local Congolese NGO, Africa Resources Watch to bring ASM cobalt miners’ perspectives into the responsible supply chain debate. We published research on corporate sourcing of artisanal cobalt in the DRC in 2021 and we are currently analysing local contracts and governance of the cobalt sector.

Lithium is another key mineral for a green transition. Around 35% of the world’s Lithium deposits are in Chile, which has a range of important ecological areas alongside high levels of income inequality and around 10% of the population living below the poverty line. Lithium mining is large scale, but like cobalt there is potential for mining to expand responsibly. Lessons from our work on the community and environmental impacts of large-scale mining could help here.

For example, in Mali we found that supporting civil society organisations to influence the design and implementation of the new mining law, taxation of large-scale mining and governance of the newly created local development funds had the potential to deliver improvements for communities around mines. We have also developed a tool in partnership with Colombia University’s Centre for Sustainable Investment covering laws and agreements on community development obligations in over 50 countries more transparent to inform the design and implementation of new laws Community Development in Mining Collection.

If the green energy transition is to live up to its ‘Just’ ambitions then the perspectives of miners and mining communities must be brought to the table when industry guidelines and government regulations are being developed. The initiatives discussed above offer a way to do this so they need to be scaled up and expanded.

- Laura Kelly is the Director of the Shaping Sustainable Markets group at the International Institute of Environment and Development, our parent organisation.

Footnotes

US White House, Fact Sheet: Securing a Made in America Supply Chain for Critical Minerals, February 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/bri...